by Benjamin Scott Wright

Dec. 14, 2020

This article was originally published on the State Bar of Wisconsin’s Elder Law and Special Needs Blog.

In Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End, Dr. Atul Gawande writes about how often medicine fails the elderly and those with terminal illness.

His first example is a man who chose a surgery that didn’t stand a chance of giving him what he really wanted (“his continence, his strength, the life he had previously known”). Despite seeing his wife die in intensive care and resolving to avoid the same fate, the man chose a risky surgery that led, 14 days later, to exactly that.

To Gawande, the remarkable thing was not the poor choice; it was that the man’s medical team “all avoided talking honestly about the choice before him.”

The same problem exists in elder law.

How often do we glide over hard questions and big decisions when we talk to clients about their estate plan? If terminal, do you want life support? Please answer after 10 minutes of discussion. How often do we give clients exactly what they’ve asked for (after we recommend it)—a lawsuit, Medicaid benefits, a trust—without stopping to consider if it will give them what they really want?

The Biggest Regret of My Career

Early on in my elder law career, I made exactly that mistake, and I made it with my own grandfather. It started with a very simple estate planning update. He didn’t have much, but we discovered a few old life insurance policies with substantial cash value.

The lawyer I worked for thought my grandfather could get the veterans “aid and attendance” benefit if we did an irrevocable asset protection trust (this was before the VA lookback). The firm did a lot of those.

I wasn’t so sure—my grandfather was still remarkably independent for his age—but everyone I talked to was very positive and thought there was no downside (in the worst-case scenario we could still terminate the trust by consent, right?). So I ignored my gut. My grandfather, of course, would go along with whatever I thought best.

Thankfully, my grandfather remained very independent for his age until just a few months before his death. He needed daily help from family with a few things, but he did not need a constant companion. Being able to pay for an aide to come in regularly would have improved his quality of life, though, and would have relieved a lot of stress on certain family members.

But the VA benefits were delayed, and delayed again, and never materialized. Ultimately, he did need a few months of skilled nursing care at the end and we had to terminate the trust. The money was immediately consumed by overdue nursing home bills. We didn’t even manage to fund a funeral trust.

Creating an irrevocable trust had seemed like a good plan. We might have saved some money while qualifying my grandfather for a helpful benefit. Maybe a better attorney would have succeeded with the VA claim.

But looking back, it’s clear to me what I should have done. I should have listened to my gut.

I should have asked what we were saving the money for. No one needed it more than my grandfather. He should have taken the cash and spent it. He would have enjoyed a better quality of life in his final years and his family would have felt less of a burden. Then, when the money ran out, he would have had an easy application for any public benefit he needed.

All I did as a lawyer was muck things up. It’s the biggest regret of my career.

Ask: What Are We Saving the Money For?

I believe many elder law clients are like my grandfather: they trust our professional judgment and will do whatever we recommend. They are also like Gawande’s patient who chose the risky surgery. They come to us with an acute pain (or the fear of it): that $9,000 bill coming each and every month. They are terrified of what it means for their futures. They want to protect their resources. Who wouldn’t?

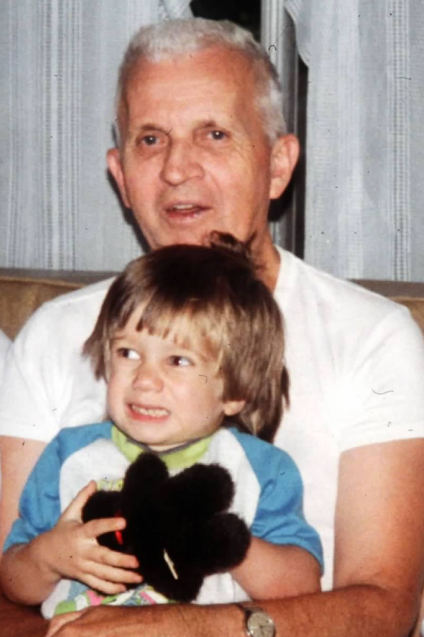

My grandfather and me

It’s easy to offer our clients financial pain relief. We can use this kind of trust and that kind of legal strategy to protect our clients’ money, make the most of their resources, and get Medicaid picking up the bill sooner. We can alleviate the symptoms. But does that cure the disease?

It depends, of course. I’ve learned to always ask that question—What are we saving the money for?

Some clients put a high priority on protecting an inheritance for their descendants and preserving the savings they’ve worked hard for their entire lives.

Yet, many clients, I’ve learned, are really concerned about having what they need for their own lives, making things simple for their families, and maintaining their independence. They tell me it won’t bother them if their children end up without an inheritance.

Like my grandfather, they are often better off making peace with spending the large amount of money needed for health care at the end of their lives, knowing that Medicaid and other benefits will be there if and when the money runs out.

This approach maximizes their independence, control, and options. And it’s usually easier on them and their families.

Being Better at Our Art: Talk Honestly

As lawyers, our job is to advise our clients. We help them make good decisions by matching their legal options to their goal. Identifying that goal is itself an art, and one our clients often need help with.

Gawande’s patient chose a surgery that was never going to give him what he really wanted, while his doctors avoided talking honestly about the choice before him.

Our clients are the same. They need lawyers who will talk honestly about the choices they face and what their legal options can and can’t accomplish.

Note: I received informed consent from my grandfather’s personal representative to share this story.